Looking back to the Middle Ages may not always be a popular thing to do in the Church today, as some aspects of our past have become contentious over the centuries. Few aspects of the history of the Church are more maligned than the Crusades. The knee-jerk reaction nowadays is to use these periods in the Church’s history as a cudgel to berate Christians for “intolerance” and to illustrate allegedly violent deeds done in the name of Christ. Rather than shy away from these events, I believe we should take the opposite approach and embrace the history of our Mother Church. Our battlefields today are different from those of our spiritual ancestors, but the lessons of great warriors of the faith have bearing today.

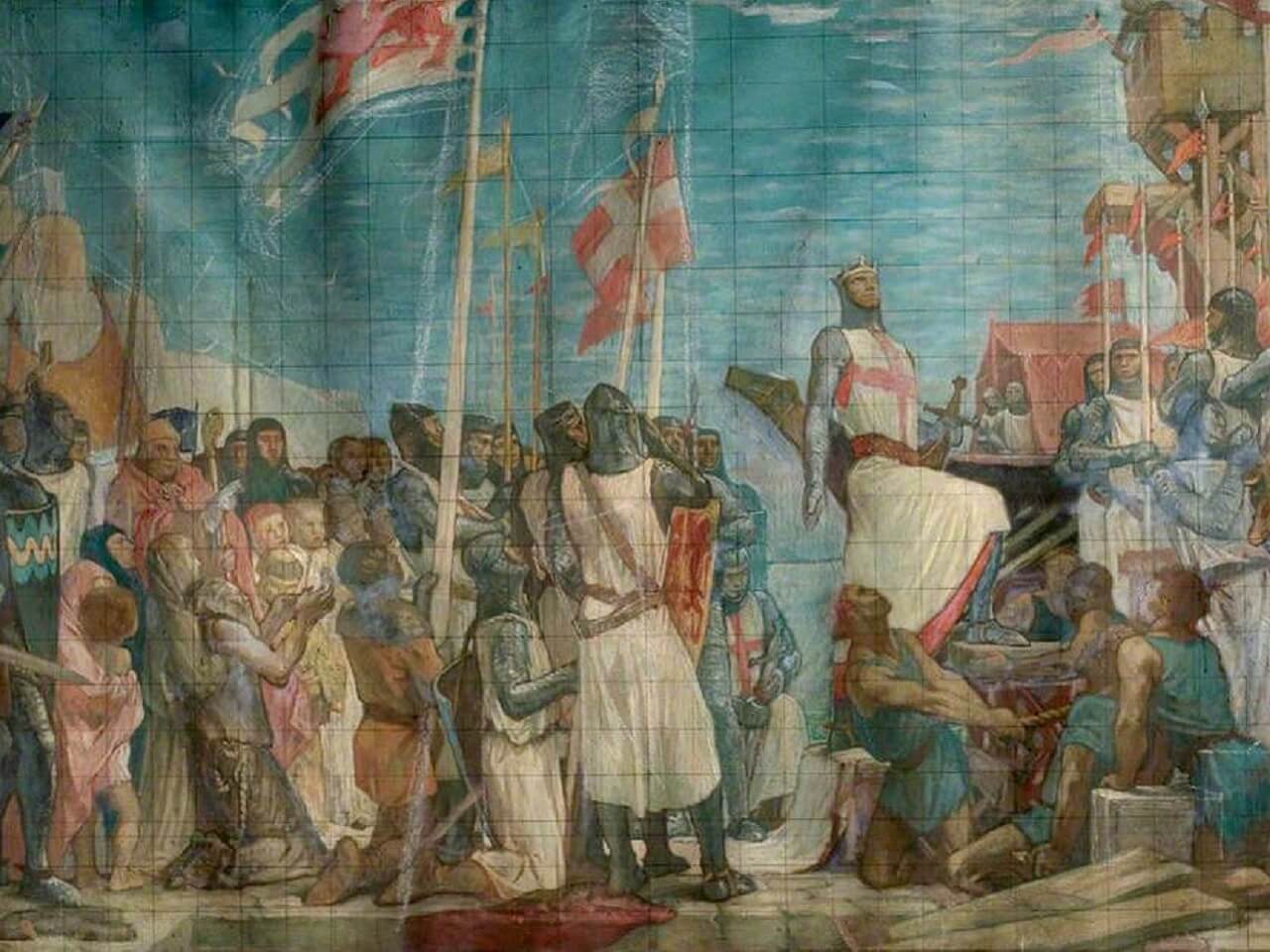

A shining example of courage in the Lord can be seen in the life of King Richard the Lionheart. Too often we are given a view of the Crusades as comprising greedy and violent Christians, drunk with bloodlust, viciously fighting the peaceable Muslims in the Middle East. Permit me to paint a different picture for you.

Life and Times of a Crusader King

Take a trip back in time to the Angevin empire and the turmoil surrounding the death of St. Thomas of Canterbury [1]. In 1157, King Henry II and Eleanor of Aquitaine gave birth to their third son, Richard. Little is known about his childhood, but it had to have some significant upheavals, evidenced by the fact that he, his brothers, and his mother would eventually rebel against his father, the king of England [2]. During a pause in the fighting in 1183, Richard’s older brother, Henry the Young King, died of dysentery at age 28, leaving Richard as the heir apparent to the throne of England. After the death of the Young Henry, Henry II demanded that Richard hand over his land holdings in Aquitaine so that the region would be left to his younger brother, John. Richard refused this demand, and in 1187, he allied with Phillip II of France to bolster his position. Amid all of this battling and bickering in England and France, events half a world away were unfolding in a rather unfortunate way for the Church and Christians all over.

In the same year, 1187, Saladin led the Saracens (Muslims) to victory at the Battle of Hattin. The loss of Jerusalem was a serious blow to the West, and the Saracens added blasphemy to the picture by fixing the True Cross upside down on a lance that was sent out to Damascus [3]. Word of this reached Tours, France, where Richard was at the time, and he promptly took the cross.

Until this point and even a few years afterward, Richard was not seen as an overly pious man. He was coronated as the king of England in 1189 when he took a vow to renounce his former life and devote himself to being worthy of taking the cross. He and Phillip II agreed to undertake the Third Crusade and went about securing their kingdoms and preparing for the long and perilous journey east. Calming the veritable rats’ nest of kings and noblemen long enough to undertake a protracted military campaign in a far off land is enough to make a legend of anyone, but this is just the start of what would make a legend of the Lionheart.

Crusading, like modern military engagements, was an expensive ordeal. To begin the journey, the king had to raise funds; encourage allies to join forces; arrange transport for thousands of soldiers and hundreds of knights; and motivate the fighting men, nobles, and knights to take the Cross for the Lord and His cause. Kings and knights had to be convinced to take out large loans in order to finance their journey.

The hero needs a villain or two in order to captivate the world, and King Richard had plenty to choose from. Shortly after setting out on the Third Crusade, one of Richard’s ships, carrying his fiancée, the Lady Berengaria, ran aground in Cyprus in 1191. The island was ruled by Isaac Comnenus, known to raid his own lands, torture his subjects, rape women, and defile virgins [4]. Isaac imprisoned Richard’s men, impounded his treasure, and held his fiancée, refusing to let the Crusader be on his way. On a failure to negotiate, Richard sacked the island fortress, liberated the citizens, and rescued his bride to be. He even had a sense of humor: when Isaac agreed to surrender on terms that Richard not put him in irons, Richard arrested him with silver chains instead.

While taking Cyprus was strategic, this was not the goal of the young king. He was eager to be off to the Holy Land. Richard married Berengaria on Cyprus and soon left with her, sailing toward Acre. This would be the first major victory of the Third Crusade. Richard and his allies conquered Acre in 1191 in June, even though Richard was ill with scurvy. Phillip II sailed home for France in poor health, and Richard was left the only king in the campaign. He is said to have fought valiantly and stayed in the Holy Land after the battle to press onward.

Richard developed quite the reputation while on the trail toward Jerusalem. Rodney Stark notes in his book God’s Battalions the following:

“Richard was a complex character”: ‘As a soldier he was little short of mad, incredibly reckless and foolhardy, but as a commander he was intelligent, cautious, and calculating. He would risk his own life with complete nonchalance, but nothing could persuade him to endanger his troops more than was absolutely necessary.’ Troops adore such a commander.” [5]

It was on this route that Richard had a chance to showcase his inner tactician. The qualities that had made him a successful nobleman back home were put to a new use here. He knew his enemy, Saladin, and knew his own strengths. Previous Crusader armies had succumbed to the temptation to engage the Saracens after one of the latter’s infamous hit-and-run barrages. Richard kept his men in tight formations, including the cavalry, and let the Saracens come to them. This led to heavy losses among the Muslim armies, especially since the crossbows of the Crusaders were far superior to the short bows of their opponents. More great victories came in the Battle of Arsuf and the taking of Jaffa. Then the Crusaders stationed in Ascalon to refortify pending negotiations with Saladin.

Internal strife among the commanders of the French along with the assassination of the newly elected king of Jerusalem saw the beginning of the end of the Third Crusade. Richard and his men won a second battle at Jaffa against Saladin that increased the legendary status of the young king in the eyes of his enemies [6]. Richard’s brother John was conspiring against him back home, and the Frankish forces led by the Duke of Burgundy were growing impatient. Richard knew that Jerusalem was impossible to hold without a constant presence in the Holy Land, reinforcements from the sea, and strong crusader states in the region. He sought to force a treaty between the Crusaders and Saladin by sacking Egypt, but he failed to take enough ground. Saladin was having a rough go of things as well and agreed in September of 1192 to allow Christian pilgrims and merchants free access to Jerusalem. Again, sick with scurvy, Richard and his armies started the long and perilous journey home, with the king held captive a number of times on the way.

The king lived out his remaining years the way he had during the wars in the East. He fought the French, who had, in collusion with his younger brother John, attempted to seize his lands while he was away. He forgave his brother in 1194 and took back control of his country in 1197 and 1198. In 1199, while suppressing a rebellion in his territory at Limousin, he was shot in the arm by a boy from the city. The boy, having shot a king, expected to be executed. However, true to his chivalrous nature, Richard forgave the young man and died of gangrene in his wound a few days later on April 6, 1199. Richard was one of the first kings who was also a knight, and he dedicated his life to fighting in the cause of the Lord.

How We Can Apply His Life Lessons

The Bible tells us, “Whosoever shall seek to save his life, shall lose it: and whosoever shall lose it, shall preserve it” [7]. I often think on the Crusaders when reflecting on this verse – the things they must have seen, the families they must have missed, the cause they may have doubted. These brave soldiers risked all, and thousands lost their lives, in order to save the West and possibly the world from Muslim rule.

Fighting is not all that Crusading was all about, though. The Lionheart teaches us about diplomacy, prudence, valor, negotiation, and strategy. All of these things help us in our daily interactions, particularly when we encounter those who spend their days fighting the Church and her teachings.

One of the chief lessons that can be learned from the life of King Richard is the virtue of sacrifice. The man who famously said, “I would sell London itself if only I could find a rich enough buyer” sacrificed a great deal to fight for the cause of the Church. How often do we find ourselves reluctant to attend Mass on Sunday or a holy day? We should be eager to make this small sacrifice of time when knights of Richard’s era sold or took loans on all they owned to fight for what they believed in. How often do we fail to financially support our parish? How often do we fail to give up our time to volunteer in our community? Little things like this will make a difference in our lives as well as in the vibrant life of the Church.

Richard showed us, in his dealings with Isaac Comnenus, that compromise is not always something to be desired. He saw the evil in the man and his rule and would have none of it. There is no dealing with devils, yet we find ourselves supporting politicians who make deals with the likes of Cecile Richards and the monsters at Planned Parenthood.

The Lionheart pressed his advance into the Holy Land and showed the Saracens that the Church is not to be trifled with. Many of us, myself included, often back down when the tenets of our faith are under attack. Some of us, like Cardinal Marx, seek to, when under attack by the homosexual lobby, open the doors toward the blessing of same-sex couples. But the Church was founded on Jesus, Who is the Truth, and the Truth does not mix with lies.

Richard, in his advances up the coast near Acre, showed us how to fight on our own terms. Often in debates, we see those on the side of the truth use the rhetorical devices of the opposition. This weakens our position and is an implicit lie. The most egregious examples come when dealing with the LGBT lobby and the abortion lobby. We let them get away with using terms like “pro-choice,” “termination of pregnancy,” “anti-LGBT,” “homophobic,” etc. Using their terms gives them the upper hand. Don’t play the game. Watch the language and keep all terms in accordance with the truth and with the Church. The opposition calls us “science deniers” when in reality we deny scientism. The distinction is important because the Church gives us science as the noble pursuit of the study of God’s works.

Valor is found not only in physical battle. Valor is what we are called to every day. When we fail and fall, we are called to persevere. Sometimes it is the strength to refuse to compromise. Sometimes it is the prudence to hold the line while the enemy advances. It is not to retreat in the hopes that things will get better without you.

Culture is the battlefield of Western nations today. We may not ever be called to take up arms in defense of the Church, but we are here to fight in other ways. The world needs the Church, and we need the courage to support her. The greatest courage is to know that we will lose and to fight anyway. All victories in this world are temporary until the Lord returns in glory.

Remember the Lionheart in your battles in this world. Take up your cross daily, and help others who are down. Take the offensive, and guard your flanks.

Notes

[1] The Annals of Roger de Hoveden: Comprising the History of England and of Other Countries of Europe from A.D. 732 to A.D. 1201 (1853, H.G. Bohn Press, London) (Pages 324-330)

[2] Richard the Lionheart, John Gillingham (1978, Times Books) (Page 64)

[3] A Concise History of the Crusades, Thomas Madden (2000) (Page 460)

[4] God’s Battalions, Rodney Stark (2009) (Page 207)

[5] God’s Battalions, Rodney Stark (2009) (Page 208 [internal citations omitted])

[6] Saladin Or What Befell Sultan Yusuf, Baha’ al-Din Yusuf Ibn Shaddad (1897)

[7] Luke 17:33 Douay-Rheims Bible