Above: Upside down Pyramid, Bratislava.

Like a piece of upside-down modernist architecture, the new papal apostolic letter Desiderio Desideravi: On the Liturgical Formation of the People of God is daringly balanced on one point: that the new liturgy of Paul VI is the fulfillment of the Second Vatican Council’s demand for liturgical reform in Sacrosanctum Concilium. On the truth or falsehood of this one point stands or falls the document’s entire argument. Let us quote Francis first:

It would be trivial to read the tensions, unfortunately present around the celebration, as a simple divergence between different tastes concerning a particular ritual form. The problematic is primarily ecclesiological. I do not see how it is possible to say that one recognizes the validity of the Council—though it amazes me that a Catholic might presume not to do so—and at the same time not accept the liturgical reform born out of Sacrosanctum Concilium, a document that expresses the reality of the Liturgy intimately joined to the vision of Church so admirably described in Lumen gentium. For this reason, as I already expressed in my letter to all the bishops, I have felt it my duty to affirm that “The liturgical books promulgated by Saint Paul VI and Saint John Paul II, in conformity with the decrees of Vatican Council II, are the unique expression of the lex orandi of the Roman Rite” (Motu Proprio Traditionis custodes, art 1) (n. 31).

We are called continually to rediscover the richness of the general principles exposed in the first numbers of Sacrosanctum Concilium, grasping the intimate bond between this first of the Council’s constitutions and all the others. For this reason we cannot go back to that ritual form which the Council fathers, cum Petro et sub Petro, felt the need to reform, approving, under the guidance of the Holy Spirit and following their conscience as pastors, the principles from which was born the reform. The holy pontiffs St. Paul VI and St. John Paul II, approving the reformed liturgical books ex decreto Sacrosancti Œcumenici Concilii Vaticani II, have guaranteed the fidelity of the reform to the Council.[1] For this reason I wrote Traditionis custodes, so that the Church may lift up, in the variety of so many languages, one and the same prayer capable of expressing her unity. As I have written, I intend that this unity be re-established in the whole Church of the Roman Rite (n. 61).

It seems, in keeping with the old saying “a bishop never has a bad meal and never hears the truth,” that some well-meaning servitors in the Vatican have been hiding from the pope and his entourage a truth that is known to millions of others: this belief in the Novus Ordo as the fruit of Vatican II is simply false and can be easily known to be false. Universal literacy and the internet have tidily seen to that.

The actual story is told rather well in the recent Episode II of Mass of the Ages, which appeared only a month ago and already has (as of this writing) one million and three hundred thousand views—vastly more than the number of people who will ever bother to read this latest 65-paragraph papal “reflection.”

Those who lament the dire condition of the Church’s public worship and who long for its restoration in harmony with sound tradition have long known about the massive disjunct between the provisions of the Constitution Sacrosanctum Concilium as approved by the vast majority of the Council Fathers and the actual Bugnini-Montini liturgical rites, mendaciously promulgated in the name of that Council. This is why the near-unanimous approval of Sacrosanctum Concilium turned into a bitter dispute among the bishops when they were shown the 1967 Novus Ordo at the Synod of Bishops, as depicted in the film with their actual quotations. This shows quite clearly that, when the Pope actually listened to the bishops of Vatican II and encouraged them to speak candidly, they did not give their approval to the Novus Ordo.

Cardinal Ratzinger Contradicts Pope Francis

Let’s recall a few of the more poignant admissions of this rather fundamental problem, beginning with Joseph Ratzinger, who, last I checked, had served as the 265th Supreme Pontiff, and who still, mysteriously, abides at the Vatican as a silent reproach to his wayward successor.

In a 1976 letter to Prof. Wolfgang Waldstein, Ratzinger expressed himself quite clearly:

The way in which the new Missal was introduced departs from previous ecclesiastical legal customs, such as those observed by Pius V in his missal reform…. The problem of the new Missal lies in the fact that it breaks away from this continuous history, which has always gone on before and after Pius V, and creates a thoroughly new book (albeit from old material), the appearance of which is accompanied by a type of prohibition of what has gone before that is quite unheard-of in the history of ecclesiastical law and liturgy. I can say with certainty from my knowledge of the Council debate and from rereading the speeches of the Council Fathers delivered at that time that this was not intended [by them].[2]

He reiterated this point in his 1986 book Feast of Faith:

In part it is simply a fact that the Council was pushed aside. For instance, it had said that the language of the Latin Rite was to remain Latin, although suitable scope might be given to the vernacular. Today we might ask: Is there a Latin Rite at all any more? Certainly there is no awareness of it.[3]

Yet, with all its advantages, the new Missal was published as if it were a book put together by professors, not a phase in a continual growth process. Such a thing has never happened before. It is absolutely contrary to the laws of liturgical growth, and it has resulted in the nonsensical notion that Trent and Pius V had “produced” a Missal four hundred years ago. The Catholic liturgy was thus reduced to the level of a mere product of modern times. This loss of perspective is really disturbing. Although very few of those who express their uneasiness have a clear picture of these interrelated factors, there is an instinctive grasp of the fact that liturgy cannot be the result of Church regulations, let alone professional erudition, but, to be true to itself, must be the fruit of the Church’s life and vitality.[4]

In 1990, Ratzinger wrote this strikingly honest assessment:

The liturgical reform, in its concrete execution, has moved further and further away from this origin [in the best of the Liturgical Movement]. The result has not been reinvigoration but devastation…. [I]n place of the liturgy that had developed, one has put a liturgy that has been made. One has deserted the vital process of growth and becoming in order to substitute a fabrication. One no longer wanted to continue the organic developing and maturing of that which has been living through the centuries, but instead, one replaced it, in the manner of technical production, with a fabrication, the banal product of the moment.[5]

There are many more passages like these, which have been gathered here. It is noteworthy that nowhere, not even once, in Francis’s Desiderio Desideravi does the quondam Vicar of Christ mention the quondam Patriarch of the West. A Jesuit whose last memory of a TLM is as a naughty altar boy in Argentina has seen fit to ignore one of the wisest and most perceptive commentators on the sacred liturgy.

More Fathers and Authorities from Vatican II Against Pope Francis

Another firsthand witness was the Austrian Cardinal Alfons Maria Stickler, who served on several commissions of Vatican II, including the one on the liturgy. He shared his detailed recollections in an important 1997 address:

Through an obligation I did not seek, then, I experienced Vatican II from the very beginning.… I understood precisely, therefore, the wishes of the Council fathers, as well as the correct sense of the texts that the Council voted on and adopted. You can understand my astonishment when I found that the final edition of the new Roman Missal [1969] in many ways did not correspond to the Conciliar texts that I knew so well, and that it contained much that broadened, changed or even was directly contrary to the Council’s provisions. Since I knew precisely the entire proceeding of the Council, from the often very lengthy discussions and the processing of the modi up to the repeated votes leading to the final formulations, as well as the texts that included the precise regulations for the implementation of the desired reform, you can imagine my amazement, my growing displeasure, indeed my indignation, especially regarding specific contradictions and changes that would necessarily have lasting consequences.[6]

He relates that Cardinal Benno Gut agreed completely with his critique. Cardinal Stickler proceeds to demonstrate systematically the numerous ways in which the Novus Ordo openly departs from the desiderata of the Council Fathers as given in Sacrosanctum Concilium. Just one example:

After a discussion lasting several days, in which arguments for and against were discussed, the Council fathers came to the clear conclusion—wholly in agreement with the Council of Trent—that Latin must be retained as the language of cult in the Latin rite, although exceptional cases were possible and even welcome…. Article 116 speaks extensively about Gregorian chant, noting that it has been the classical chant of the Roman Catholic liturgy since the time of Gregory the Great, and as such must be retained…. As the subject of the language of worship was discussed in the Council hall over the course of several days, I followed the process with great attention, as well as later the various wordings of the Liturgy Constitution until the final vote. I still remember very well how after several radical proposals a Sicilian bishop rose and implored the Fathers to allow caution and reason to reign on this point, because otherwise there would be the danger that the entire Mass might be held in the language of the people—whereupon the entire hall burst into uproarious laughter.

His Eminence insists:

Never has there been, therefore, in any of the Christian-Catholic rites, a break, a radically new creation—with the exception of the post-Conciliar reform. But the Council again and again demanded for the reform a strict adherence to tradition. All reforms, beginning with Gregory I through the Middle Ages, during the entry into the Church of the most disparate peoples with their various customs, have observed this ground rule.

Archbishop Robert J. Dwyer of Portland, present at all four sessions of the Council, wrote in a newspaper article on July 9, 1971:

The great mistake of the Council Fathers was to allow the implementation of the Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy to fall into the hands of men who were either unscrupulous or incompetent. This is the so-called “Liturgical Establishment,” a Sacred Cow which acts more like a White Elephant as it tramples the shards of a shattered liturgy with ponderous abandon.[7]

On October 26, 1973, His Excellency voices his grief:

Who dreamed on that day [when SC was promulgated] that within a few years, far less than a decade, the Latin past of the Church would be all but expunged, that it would be reduced to a memory fading into the middle distance? The thought of it would have horrified us, but it seemed so far beyond the realm of the possible as to be ridiculous. So we laughed it off.[8]

In like manner, the Council Father Msgr. Domenico Celada wrote in Lo Specchio of July 29, 1969:

I regret having voted in favor of the Council constitution in whose name (but in what a manner!) this heretical pseudo-reform has been carried out, a triumph of arrogance and ignorance. If it were possible, I would take back my vote, and attest before a magistrate that my assent had been obtained through trickery.

Such quotations could be easily multiplied.

Back in 2006, Alcuin Reid published a paper, “The Fathers of Vatican II and the Revised Mass: Results of a Survey,” in which he shared with the public responses he had received from still-living participants in the first session of the Council.[9] A frequent refrain is that what followed the Council was not what these bishops had in mind or had anticipated. Some expressed bitter regret at having been “played” and others rejoiced in the audacity of a postconciliar reform that far outstripped its brief, but no one simply said: “Yes, this is what we voted for.”

We can see this simply by inspecting what the Council Fathers actually said about retaining Latin in the liturgy. Contrary to Pope Francis’s inventive narration, it is easy to show that only a small and obnoxious minority at the Council pushed hard for total vernacularization. For the vast majority, this was completely out of the question. I have gathered a huge number of quotations from the aula speeches in an article “The Council Fathers in Support of Latin: Correcting a Narrative Bias.”

The Desperation of the False Narrative

As I and others have written concerning the Traditionis Custodes campaign (and, particularly, Archbishop Roche’s contributions to it), the strategy of the enemies of tradition is quite simple—and quite desperate. In the words of canceled priest Fr. Bryan Houghton: “You do not just tell a lie but the exact opposite of the truth; it leaves your opponent speechless. It is the technique used so successfully by progressives when they accuse traditionalists of being divisive.”[10] The great lie here is that the liturgical reform of the late 1960s is “what Vatican II demanded,” and that if anyone refuses to embrace it passionately, he is guilty of “dissenting from the Council.” The difference in 2022 is that, rather than leaving us speechless, this lie provokes today a thunderous response from both “conservative” and “traditionalist” Catholics. Like the lie on which Roe v. Wade was founded, the lie at the heart of Bergoglio v. Tradition will also crumble one day, when the false narrative becomes impossible to sustain any longer.

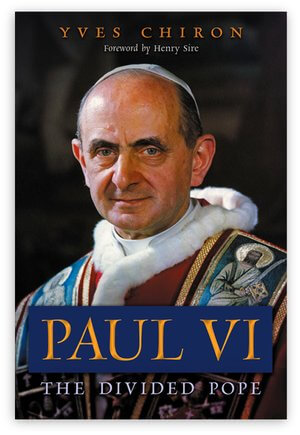

As if on cue, Angelico Press has just released an English translation of Yves Chiron’s magnificent biography Paul VI: The Divided Pope, in which we discover (among other things) just how willing that pope was to allow himself a mile for every inch given by the Council, or, in plain language, to do as he pleased, regardless of what the Council specified. That is why we suffer under a liturgy patently at odds with or in tension with most of what is to be found in Sacrosanctum Concilium; and why, more broadly, there is an unending liturgical war between those who follow the precept of the Apostle Paul—“maintain the traditions” (1 Cor 11:2), “stand firm and hold to the traditions” (2 Thess 2:15)—and those who follow the liquefying aggiornamento of the Age of Aquarius.

As if on cue, Angelico Press has just released an English translation of Yves Chiron’s magnificent biography Paul VI: The Divided Pope, in which we discover (among other things) just how willing that pope was to allow himself a mile for every inch given by the Council, or, in plain language, to do as he pleased, regardless of what the Council specified. That is why we suffer under a liturgy patently at odds with or in tension with most of what is to be found in Sacrosanctum Concilium; and why, more broadly, there is an unending liturgical war between those who follow the precept of the Apostle Paul—“maintain the traditions” (1 Cor 11:2), “stand firm and hold to the traditions” (2 Thess 2:15)—and those who follow the liquefying aggiornamento of the Age of Aquarius.

One thing I have noticed more and more is how often our church officials these days end up parodying themselves, or end up uttering the truth rather as the high priest Caiaphas did, in spite of himself (cf. Jn 11:50). Thus speaks the Holy Father in Desiderio Desideravi:

The non-acceptance of the liturgical reform, as also a superficial understanding of it, distracts us from the obligation of finding responses to the question that I come back to repeating: how can we grow in our capacity to live in full the liturgical action? How do we continue to let ourselves be amazed at what happens in the celebration under our very eyes? We are in need of a serious and dynamic liturgical formation (n. 31).

I, for one, foresee little difficulty in many Catholics continuing to let themselves be amazed at what happens in the celebration of the Novus Ordo, under their very eyes. Indeed, that, for many, truly is the start of a “serious and dynamic liturgical formation,” which finds its fulfillment in reclaiming their Roman Catholic birthright.

A good friend of mine summed up this apostolic letter as follows: “A lot of glittering generalities, a few typically Bergoglian poorly-informed insults (‘Pelagians! Neo-Gnostics!’), and one repetition of the lie that the post-Conciliar liturgy has anything to do with the Council or Sacrosanctum Concilium. Like most works of its genre, it brings nothing to the table, and will be swiftly forgotten.” It’s a sort of capstone (or might one say, headstone?) of this pope’s progressivist liturgical fantasies. Our Catholic sensus fidei rightly inclines us to ignore the aquarian-antiquarian rantings of an unhinged pope.[11] After all, he himself assures us that this document has little or no magisterial standing:

I simply desire to offer some prompts or cues for reflections that can aid in the contemplation of the beauty and truth of Christian celebration. (n. 1)… In this letter I have wanted simply to share some reflections which most certainly do not exhaust the immense treasure of the celebration of the holy mysteries (n. 6).

Vatican News described it thus: “It is not a new instruction or a directive with specific norms, but rather a meditation on understanding the beauty of liturgical celebration and its role in evangelization.” Well, then, may the meditation be of value to those who have nothing better to meditate with. More succinctly, let the dead bury the dead. As for me and my house, we will serve the Lord in the beauty of holiness and in the beauty of Catholic Tradition.

[1] The official English translation is incorrect here in saying “of the Council”; the Italian has al Concilio.

[2] In Wolfgang Waldstein, “Zum motuproprio Summorum Pontificum,” in Una Voce Korrespondenz 38/3 [2008], 201–214, my translation: “die Art der Einführung des neuen Missale von den bisherigen kirchlichen Rechtsgewohnheiten abweicht, wie sie etwa Pius V bei seiner Messbuch-Reform einhielt… Das Problem des neuen Missale liege demgegenüber darin, daß es aus dieser kontinuierlichen, vor und nach Pius V immer weitergegangenen Geschichte ausbricht und ein durchaus neues Buch (wenn auch aus altem Material) schafft, dessen Auftreten mit einem der kirchlichen Rechts- und Liturgiegeschichte durchaus fremden Typus von Verbot des Bisherigen begleitet ist. Ich kann aus meiner Kenntnis der Konzilsdebatte und aus nochmaliger Lektüre der damals gehaltenen Reden der Konzilsväter mit Sicherheit sagen, daß dies nicht intendiert war.”

[3] The Feast of Faith: Approaches to a Theology of the Liturgy, trans. Graham Harrison (San Francisco:

Ignatius Press, 1986), 84.

[4] Ibid., 86–87.

[5] This passage is quoted in many different versions (see Sharon Kabel’s research), but the one here is an exact translation of the original source: see Theologisches, 20.2 (Feb. 1990), 103–4, citing the commentary in Simandron—Der Wachklopfer. Gedenkschrift für Klaus Gamber (1919-1989), ed. Wilhelm Nyssen (Cologne: Luthe-Verlag, 1989), 13–15.

[6] “Recollections of a Vatican II Peritus,” first published in 1999 in Latin Mass magazine, republished today, June 29, 2022 at New Liturgical Movement.

[7] The Tidings, July 9, 1971, cited in Michael Davies, Pope Paul’s New Mass (Kansas City, MO: Angelus Press, 2009), 651.

[8] Twin Circle, October 26, 1973; cited in Michael Davies, Liturgical Timebombs in Vatican II (Rockford, IL: TAN Books, 2003), 65. In writing this he verifies Cardinal Stickler’s recollection of the laughter at the Council.

[9] Antiphon 10 (2006): 170–90.

[10] Unwanted Priest: The Autobiography of a Latin Mass Exile (Brooklyn: Angelico Press, 2022), 158.

[11] See Gregory DiPippo, “The Revolution Is Over,” NLM, August 1, 2021; idem, “The Last Stand of the Brezhnev Papacy,” NLM, December 18, 2021; “What Is an Ideology?,” NLM, May 6, 2022.