Like many Catholics who love their faith, I have struggled to find an explanation for the current crisis in the Church. Despite countless hours of research and analysis, I still find the situation deeply mysterious. It seems that the impossible has happened. It seems that the Church has lost either its visibility or its indefectibility. I know on faith that the Church must always retain these characteristics, but I do not always understand how she has done so in our present circumstances.

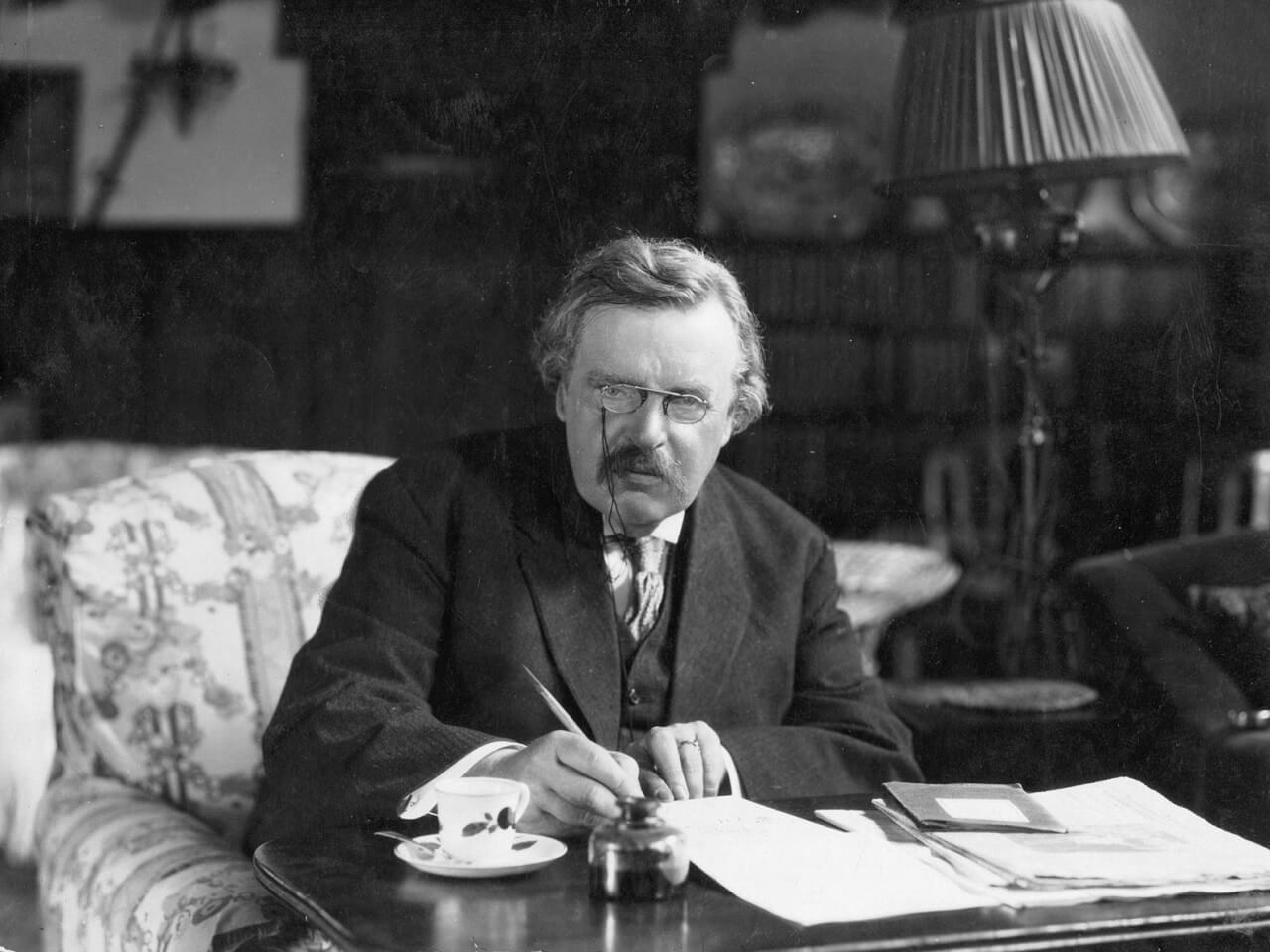

Recently, I was listening to a recording of a work by the great 20th-century Catholic writer, G. K. Chesterton. The work is entitled The Everlasting Man. Although Chesterton did not live to see our dark hour in Catholicism, he did pen the following passage in that book, which struck me as eminently relevant to our time.

Indeed the Book of Job avowedly only answers mystery with mystery. Job is comforted with riddles; but he is comforted. Herein is indeed a type, in the sense of a prophecy, of things speaking with authority. For when he who doubts can only say “I do not understand,” it is true that he who knows can only reply or repeat “You do not understand.” And under that rebuke there is always a sudden hope in the heart; and the sense of something that would be worth understanding [i].

Here, Chesterton explores the reality of the divine paradox or mystery. It has different names and different aspects, including what Catholic novelist JRR Tolkien calls “the long defeat.”

Then there is The Ballad of the White Horse. This poem tells the story of King Alfred the Great and his fight against the invading pagan Danes, who had pretty much taken over his kingdom. The story is based in history, and tradition says that, in one of his moments of despair over ever repelling the invaders and taking back his kingdom, King Alfred had a vision of Our Lady. This is how Chesterton narrates the scene:

In the river island of Athelney,

With the river running past,

In colours of such simple creed

All things sprang at him, sun and weed,

Till the grass grew to be grass indeed

And the tree was a tree at last.

Fearfully plain the flowers grew,

Like the child’s book to read,

Or like a friend’s face seen in a glass;

He looked; and there Our Lady was,

She stood and stroked the tall live grass

As a man strokes his steed.

Her face was like an open word

When brave men speak and choose,

The very colours of her coat

Were better than good news.

She spoke not, nor turned not,

Nor any sign she cast,

Only she stood up straight and free,

Between the flowers in Athelney,

And the river running past.

One dim ancestral jewel hung

On his ruined armour grey,

He rent and cast it at her feet:

Where, after centuries, with slow feet,

Men came from hall and school and street

And found it where it lay.

“Mother of God,” the wanderer said,

“I am but a common king,

Nor will I ask what saints may ask,

To see a secret thing.

“The gates of heaven are fearful gates

Worse than the gates of hell;

Not I would break the splendours barred

Or seek to know the thing they guard,

Which is too good to tell.

“But for this earth most pitiful,

This little land I know,

If that which is for ever is,

Or if our hearts shall break with bliss,

Seeing the stranger go?

“When our last bow is broken, Queen,

And our last javelin cast,

Under some sad, green evening sky,

Holding a ruined cross on high,

Under warm westland grass to lie,

Shall we come home at last?”

And a voice came human but high up,

Like a cottage climbed among

The clouds; or a serf of hut and croft

That sits by his hovel fire as oft,

But hears on his old bare roof aloft

A belfry burst in song.

“The gates of heaven are lightly locked,

We do not guard our gain,

The heaviest hind may easily

Come silently and suddenly

Upon me in a lane.

“And any little maid that walks

In good thoughts apart,

May break the guard of the Three Kings

And see the dear and dreadful things

I hid within my heart.

“The meanest man in grey fields gone

Behind the set of sun,

Heareth between star and other star,

Through the door of the darkness fallen ajar,

The council, eldest of things that are,

The talk of the Three in One.

“The gates of heaven are lightly locked,

We do not guard our gold,

Men may uproot where worlds begin,

Or read the name of the nameless sin;

But if he fail or if he win

To no good man is told.[ii]

The divine refusal to spell out an answer, to respond to a seemingly dire question, is of key importance here. No doubt, at this point King Alfred feels betrayed. The Lady’s message is so far hardly encouraging. It seems as though God has abandoned England to its fate, and even Our Lady will not tell the king what the outcome will be – which no doubt means that it won’t be good.

This divine silence, or rather divine riddle-making, is a theme that Chesterton wrote on extensively in his essay “The Book of Job.” This whole book of the Old Testament is really a philosophical riddle, says Chesterton, a riddle surrounding the question of suffering and failure. Job cries out to Heaven for some kind of answer, some reason for his trials. The response is not at all what he expects (emphasis added):

This, I say, is the first fact touching the speech; the fine inspiration by which God comes in at the end, not to answer riddles, but to propound them. The other great fact which, taken together with this one, makes the whole work religious instead of merely philosophical, is that other great surprise which makes Job suddenly satisfied with the mere presentation of something impenetrable. Verbally speaking the enigmas of Jehovah seem darker and more desolate than the enigmas of Job; yet Job was comfortless before the speech of Jehovah and is comforted after it. He has been told nothing, but he feels the terrible and tingling atmosphere of something which is too good to be told. The refusal of God to explain His design is itself a burning hint of His design. The riddles of God are more satisfying than the solutions of man [iii].

Such a situation as ours, where the Catholic Church seems overwhelmed by her enemies, seems to have lost her essential characteristics, is certainly a riddle. The reality is that in fathoming the designs of God, even the mystery of iniquity, the human mind is inadequate. This is good. There is a certain relief in recognizing that some things are beyond human understanding, as is certainly the case regarding God’s design in allowing the present crisis.

Chesterton can express this whole idea far better than I, so I will let him speak again (my emphasis):

This we may call the third point. Job puts forward a note of interrogation; God answers with a note of exclamation. Instead of proving to Job that it is an explicable world, He insists that it is a much stranger world than Job ever thought it was. Lastly, the poet has achieved in this speech, with that unconscious artistic accuracy found in so many of the simpler epics, another and much more delicate thing. Without once relaxing the rigid impenetrability of Jehovah in His deliberate declaration, he had contrived to let fall here and there in the metaphors, in the parenthetical imagery, sudden and splendid suggestions that the secret of God is a bright and not a sad one–semi-accidental suggestions, like light seen for an instant through the cracks of a closed door. It would be difficult to praise too highly, in a purely poetical sense, the instinctive exactitude and ease with which these more optimistic insinuations are let fall in other connections, as if the Almighty Himself were scarcely aware that He was letting them out. For instance, there is that famous passage where Jehovah, with devastating sarcasm, asks Job where he was when the foundations of the world were laid, and then (as if merely fixing a date) mentions the time when the sons of God shouted for joy (38:4-7). One cannot help feeling, even upon this meager information, that they must have had something to shout about. Or again, when God is speaking of snow and hail in the mere catalogue of the physical cosmos, he speaks of them as a treasury that He has laid up against the day of battle – a hint of some huge Armageddon in which evil shall be at last overthrown. …

The book of Job is chiefly remarkable, as I have insisted throughout, for the fact that it does not end in a way that is conventionally satisfactory. Job is not told that his misfortunes were due to his sins or a part of any plan for his improvement. But in the prologue we see Job tormented not because he was the worst of men, but because he was the best. It is the lesson of the whole work that man is most comforted by paradoxes. Here is the very darkest and strangest of the paradoxes; and it is by all human testimony the most reassuring. I need not suggest what high and strange history awaited this paradox of the best man in the worst fortune. I need not say that in the freest and most philosophical sense there is one Old Testament figure who is truly a type; or say what is prefigured in the wounds of Job. [iv]

So we see that, according to Chesterton, recognizing and admitting God’s supremacy of understanding and governance are inseparable from allowing optimism back into our minds. We first accept the darkness of confusion and apparent contradiction and God’s silence. We accept that we cannot explain it; only God can. Only then do the rays of hope begin to seep back into the sky.

When we accept the mystery of the situation, we receive suddenly, as a bonus, the thrill of possibility that the mystery, however mysterious, might actually be a happy mystery in the end. It might not be a question of resignation in the sense of resigning ourselves to darkness, suffering, and failure, or not solely that – it might be a question of resigning ourselves to an unspeakable triumph.

It might be. In the meantime, we seem to be faced with defeat. In one of his letters, JRR Tolkien wrote, “Actually I am a Christian, and indeed a Roman Catholic, so that I do not expect ‘history’ to be anything but a ‘long defeat’ – though it contains (and in legend may contain more clearly and movingly) some samples or glimpses of final victory” [v]. That is what history often appears to be, including our history: a long, slow, painful defeat as the devil and his forces wage merciless war against the saints.

A wise man might say he’s had enough with all these circular argument and counter-arguments about the Church. A wise man might look at the Church today and laugh at its claims of Divine institution. He might just give up.

But we are not wise, and we never claimed to be, and we never wanted to be. We believe that a Man executed by the Romans 2,000 years ago is God. We believe that we drink His Blood and eat His Flesh. The words of St. Paul are especially powerful in this context: “For seeing that in the wisdom of God the world, by wisdom, knew not God, it pleased God, by the foolishness of our preaching, to save them that believe. For both the Jews require signs, and the Greeks seek after wisdom: But we preach Christ crucified, unto the Jews indeed a stumblingblock, and unto the Gentiles foolishness: But unto them that are called, both Jews and Greeks, Christ the power of God, and the wisdom of God. For the foolishness of God is wiser than men; and the weakness of God is stronger than men” (1 Corinthians 1:21-25).[vi] And in the end, it is we who are wise, and the world that is foolish. “Let no man deceive himself: if any man among you seem to be wise in this world, let him become a fool, that he may be wise. For the wisdom of this world is foolishness with God. For it is written: I will catch the wise in their own craftiness. And again: The Lord knoweth the thoughts of the wise, that they are vain” (1 Corinthians 3:18-20). Our Lord himself said, “Amen I say to you, unless you be converted, and become as little children, you shall not enter into the kingdom of heaven” (Matthew 18:3).

Returning to King Alfred, Chesterton dramatizes this same idea, glorying in the “foolishness” of Christians. This is Our Lady speaking to the king again.

“The men of the East may spell the stars,

And times and triumphs mark,

But the men signed of the cross of Christ

Go gaily in the dark.

“The men of the East may search the scrolls

For sure fates and fame,

But the men that drink the blood of God

Go singing to their shame.

“The wise men know what wicked things

Are written on the sky,

They trim sad lamps, they touch sad strings,

Hearing the heavy purple wings,

Where the forgotten seraph kings

Still plot how God shall die.

“The wise men know all evil things

Under the twisted trees,

Where the perverse in pleasure pine

And men are weary of green wine

And sick of crimson seas.

“But you and all the kind of Christ

Are ignorant and brave,

And you have wars you hardly win

And souls you hardly save.

“I tell you naught for your comfort,

Yea, naught for your desire,

Save that the sky grows darker yet

And the sea rises higher.

“Night shall be thrice night over you,

And heaven an iron cope.

Do you have joy without a cause,

Yea, faith without a hope?” [vii]

It is only in this context – in a framework of joy without cause and faith without hope and ignorant foolishness and an utterly lost cause – that the long defeat pointed out by Tolkien can itself be defeated. Tolkien writes in his essay “On Fairy Stories” of a phenomenon he calls the “eucatastrophe,” or surprise happy ending, “a sudden and miraculous grace: never to be counted on to recur. It does not deny the existence of dyscatastrophe, of sorrow and failure: the possibility of these is necessary to the joy of deliverance; it denies (in the face of much evidence, if you will) universal final defeat and in so far is evangelium, giving a fleeting glimpse of Joy, Joy beyond the walls of the world, poignant as grief.”[viii] Such a miracle is possible only when all hope seems lost – in our case, when the Church seems to have truly failed and the divine riddle unanswerable. The revelation of the secret of God will be a true revelation only if it has been a true secret.

The principle of the spiritual life that in failure is the beginning of grace might hold true in a more cosmic sense, then, even in terms of the apparent “failure” of the Church. The whole of the Christian religion is built on this principle: that in defeat is victory, in weakness strength. The words of St. Paul may well be the words of the Church herself: “And he said to me: My grace is sufficient for thee; for power is made perfect in infirmity. Gladly therefore will I glory in my infirmities, that the power of Christ may dwell in me. For which cause I please myself in my infirmities, in reproaches, in necessities, in persecutions, in distresses, for Christ. For when I am weak, then am I powerful” (2 Corinthians 12:19).

And yes, King Alfred and his followers did miraculously defeat the Danes and take back the kingdom.

[i] G.K. Chesterton, The Everlasting Man (A.P. Watt Ltd, 1925; reprint, San Francisco: Ignatius, 2008), 98.

[ii] G.K. Chesterton, The Ballad of the White Horse (New York: John Lane Company, 1911; reprint, Mineola, NY: Dover, 2010), 9-12.

[iii] G. K. Chesterton, “The Book of Job,” In In Defense of Sanity, ed. Dale Alqhuist (San Francisco: Ignatius, 2011), 99.

[iv] Chesterton, “Book of Job,” 100-102.

[v] JRR Tolkien, Letter 195, In The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, ed. Humphrey Carpenter (George Allan & Unwin, 1981; reprint, New York: Houghton Mifflin, 2000), 255.

[vi] Scripture quotations taken from the Douay Rheims translation.

[vii] Chesterton, Ballad of the White Horse, 13-14.

[viii] JRR Tolkien, “On Fairy Stories,” In The Monsters and the Critics and Other Essays, ed. Christopher Tolkien (George Allan & Unwin, 1983; reprint, Harper Collins, 2006), 153.